About the Niagara River paintings

The installation at the Castellani Art Museum included paintings, drawings, items used during the creation of the work, description plaques for each painting, mural maps on three walls, a mural showing the movement of Niagara Falls as it moved upstream over the centuries and how that correlated with the history of the indigenous peoples of the region, time lapse videos and a sound file that was played during the exhibition. The above time lapse video documents the artist creating one of the paintings in the exhibition and the sound file incorporates layers of sounds collected during the creation of the project.

The paintings shown below are available for purchase before and during the exhibition through Meibohm Fine Arts (716-652-0940 /[email protected] ). Paintings purchased before April 14th, 2023 may have collectors' names included in the painting's label while the work is on exhibit at the Castellani Museum. Collectors' names can also be added to this website.

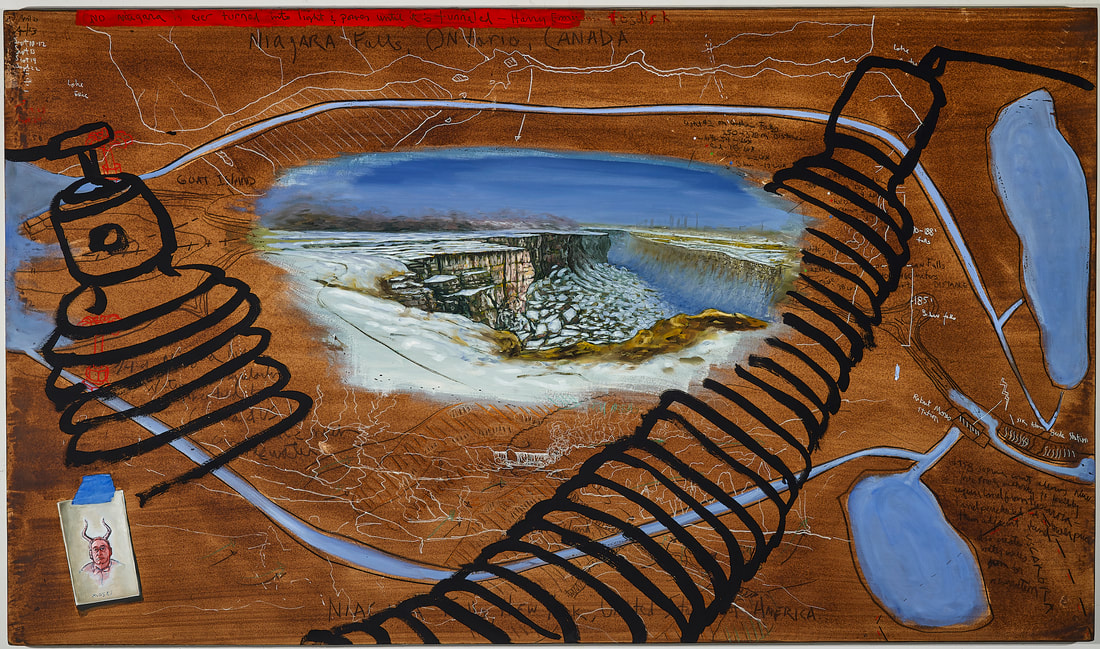

1. Biological Regionalism: Artificiality of the Niagara Falls, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

One can only imagine the awe of discovering the unharnessed beauty of Niagara Falls before the 1800’s. The wilderness of Niagara Falls started to diminish in the early nineteenth century as structures started to rise around the Falls to promote it as a tourist attraction. Soon afterwards, mills, tanneries and other businesses, fueled by its waters, were built on its banks. By 1881, Niagara Falls waters began to be diverted for hydroelectricity by both Canada and the United States and today, as much as three fourths of the water heading to the Falls is regularly diverted to hydroelectric dams located over four miles downstream. Part of the land used for the reservoir, that holds the Niagara Falls water before it is fed into the Robert Moses Generating Station, was forcibly attained from the Tuscarora Native American tribe. Robert Moses, who oversaw the project, initially offered the tribe $1000 per acre when he was offering $10,000 per acre to the adjacent property owned by Niagara University.

Over the past hundred years, Canada and the United States has had to do a great deal of excavation to the Niagara River riverbed immediately upstream of the Falls to compensate for water being diverted and its effect on the aesthetic beauty of the Falls. Weirs, walls and excavation have been created as a way to ensure that an artificially consistent column of water flows over the crest line and so the blue green water color is maintained. The mist has also been controlled over the years to create less of a nuisance for the visitors. Fill has also been added to the land bordering the river to provide the best possible views of the Falls. Goat Island was enlarged; consequently, there is no longer any part of the Horseshoe Falls that flows through the United States.

The flow of the water is turned up or down depending on the peak tourist times during the day and during the year. The water is so regulated, in fact, that the Falls could be almost completely turned off if needed.

2. Biological Regionalism: Underground Railroad of the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

The Niagara River was one of the most important routes for African Americans trying to escape slavery in the United States. There were many supporters of their efforts who were part of the Underground Railroad in the US and Canada. The Fugitive Slave Law (1850-1864) was passed by Congress legislating heavy fines of $1000 (over $37,000 today) and jail term of six-months for anyone supporting the efforts of slaves seeking refuge in Canada or in the northern states. Since the law provided no jury process to African Americans, enslaved people and free blacks found outside a slave owner's land were returned South. Harriet Tubman and many of the workers of Cataract House, which was located on the banks of Niagara Falls, were just a few of the those who were instrumental in the Underground Railroad in the Niagara Region. John Morrison, the head waiter at the Cataract House, personally ferried many escapees across to Canada while Tubman personally escorted countless others across the Suspension Bridge located upstream of the Whirlpool Rapid. Having reached the homes and businesses of the Underground Railroad supporters, the runaways tried to make it to freedom by stowing away on a steamship, rowing across in boats, walking over bridges, riding on railroad cars or even swimming across wherever possible. Many slave owners and their representatives, however, stationed themselves along the river trying to recapture any runaways. Reaching freedom was a complicated and dangerous venture for both the escapees and their guides and supporters.

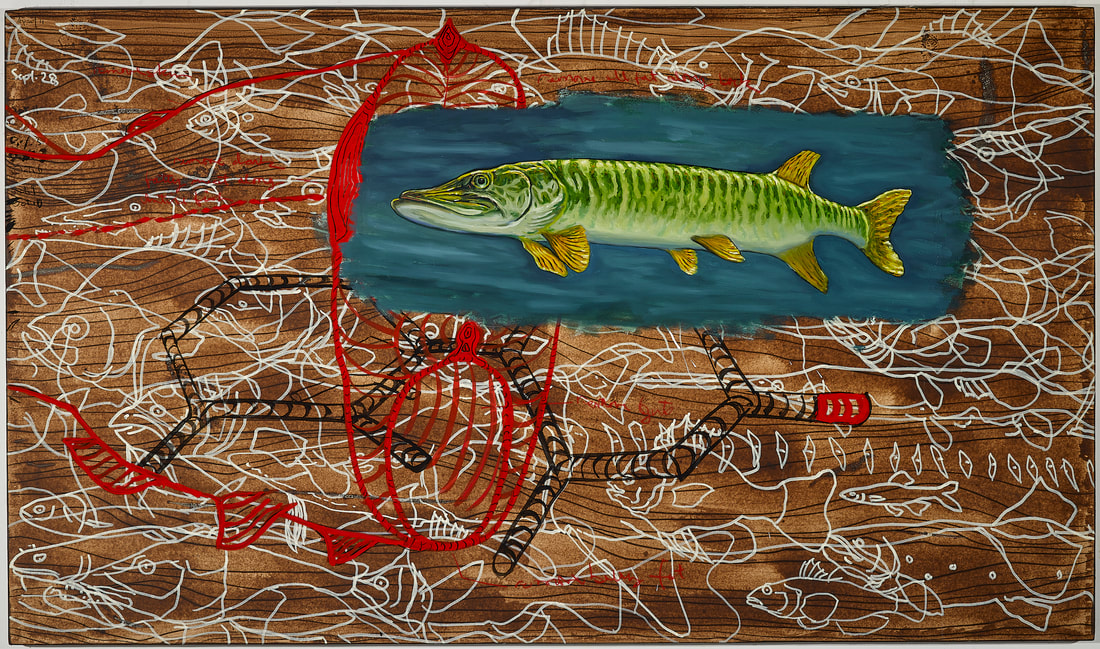

3. Biological Regionalism: Fish of the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

The Niagara River has a multitude of fish species in its waters including; sturgeon, coho salmon, chinook salmon, muskellunge, lake trout, walleye, northern pike, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, brown trout, steelhead, Atlantic salmon, channel catfish, bullhead, sucker, bluegill, white perch, yellow perch, rock bass, crappie, emerald shiner, alewife, rainbow smelt, round goby, lake whitefish, sheepshead, white bass, gizzard shad, burbot, longnose gar and sea lampreys.

It is also a sport fishing location that draws anglers from around the country to fish, as its lower river is well known for its Chinook salmon, steelhead (rainbow trout), walleye lake trout, brown trout, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, muskellunge, yellow perch and smelt. Unfortunately, however, the fish are also living in a mixture of toxins that have accumulated since the 1800's. As the river flows from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario it continues to collect toxins and sewage so that the lower Niagara is more toxic than the upper section. Although clean-up efforts by Canadian and American governments, businesses and environmental organizations have made significant improvements to the water quality since the late 1980’s, there is still enough contaminants to make it unsafe to eat many species of fish from these waters. The New York State Department of Health has made recommendations limiting consumption of some of these species due to the high levels of banned toxins such as PCBs/Dioxins (by-product from thermal and industrial processes) and Mirex (commercial insecticide) in the river. The condition of the river continues to deteriorate because of leaks from hazardous storage sites and discharges from industrial and municipal sites and sewage treatment plants. Many of these leaks and discharges are not only located along its banks but also from the many tributaries that flow into the river. Although the toxins can be found throughout the fish, they tend to accumulate in the fat deposits in the belly, the back and fatty muscle as well as in the skin and organs.

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

The Niagara River has a multitude of fish species in its waters including; sturgeon, coho salmon, chinook salmon, muskellunge, lake trout, walleye, northern pike, largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, brown trout, steelhead, Atlantic salmon, channel catfish, bullhead, sucker, bluegill, white perch, yellow perch, rock bass, crappie, emerald shiner, alewife, rainbow smelt, round goby, lake whitefish, sheepshead, white bass, gizzard shad, burbot, longnose gar and sea lampreys.

It is also a sport fishing location that draws anglers from around the country to fish, as its lower river is well known for its Chinook salmon, steelhead (rainbow trout), walleye lake trout, brown trout, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, muskellunge, yellow perch and smelt. Unfortunately, however, the fish are also living in a mixture of toxins that have accumulated since the 1800's. As the river flows from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario it continues to collect toxins and sewage so that the lower Niagara is more toxic than the upper section. Although clean-up efforts by Canadian and American governments, businesses and environmental organizations have made significant improvements to the water quality since the late 1980’s, there is still enough contaminants to make it unsafe to eat many species of fish from these waters. The New York State Department of Health has made recommendations limiting consumption of some of these species due to the high levels of banned toxins such as PCBs/Dioxins (by-product from thermal and industrial processes) and Mirex (commercial insecticide) in the river. The condition of the river continues to deteriorate because of leaks from hazardous storage sites and discharges from industrial and municipal sites and sewage treatment plants. Many of these leaks and discharges are not only located along its banks but also from the many tributaries that flow into the river. Although the toxins can be found throughout the fish, they tend to accumulate in the fat deposits in the belly, the back and fatty muscle as well as in the skin and organs.

4. Biological Regionalism: Water of the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

Although mills had been relying on Niagara River water for a hundred years before Frederic Church cropped out the developments along the river to create his iconic painting of the Falls in 1857, the dramatic deterioration of the river started two years later. A canal was dug around the Falls to power the large mills and manufacturing plants that were built just downstream of the tourist attraction. New York State encouraged the industrial development and unrestricted use of the river so that, by the end of the century, 265 manufacturing plants were creating enough water, ground and air pollution that the environment was unhealthy for the residents of the region and was creating an eyesore to the growing tourism industry. Without enforced regulations or urban planning to take care of the sewage from the growing population along the river and Lake Erie, the toxicity of the region worsened. Over the century that followed, the scale of the pollution became so insurmountable that it was impossible to secure enough funding to resolve the situation. To make matters worse, toxic contaminants continue to leak from toxic dump sites, brownfield and superfund sites. Toxic waste from industrial plants continues to flow into the river and municipalities continue to unload billions of tons of sewage into the river and its tributaries every year. This is the same river that is the source of public water for several cities. The past few decades, however, have shown that when the government supports clean-up efforts through funding, when regulatory policies are followed and enforced, and when the public is made aware of the situation, significant improvements can occur. Mussels (Elliptio complanata) filter small organic particles out of the water column and by doing so they can be used to monitor the concentrations of contaminants, to identify contaminant sources and to document effectiveness of remedial actions.

Some of the toxins you will find in the river are as follows:

Chlorobenzenes (CBs):

1,3-Dichlorobenzene

1,4-Dichlorobenzene

1,2-Dichlorobenzene

1,3,5-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,3-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,3,4-Tetrachlorobenzene

Pentachlorobenzene

Hexachlorobenzene

Organochlorine Pesticides (OCs):

α-HCH

α-Chlordane1

p,p’-DDT2

γ-HCH (lindane)

γ-Chlordane

o,p-DDT

Heptachlor

Methoxychlor

p,p’-DDE

Heptachlor-epoxide

Aldrin

Endrin Aldehyde

p,p’-TDE

β-Endosulfan

Endrin

α-Endosulfan

Dieldrin

PCBs

Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs):

2-Methylnaphthalene

1-Methylnaphthalene

Chrysene/Triphenylene

2-Chloronaphthalene

Naphthalene

Anthracene

Fluorene

Phenanthrene

Pyrene

Dibenzo(ah)anthracene

Fluoranthene

Benzo(b/k)fluoranthene 3

Benzo(a)pyrene

Indeno(123-cd)pyrene

Benzo(ghi)perylene

Acenaphthylene

Benzo(a)anthracene

Industrial By-product Chemicals:

Octachlorostyrene

Mirex

Photomirex

Hexachlorobutadiene

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene

Herbicides:

Atrazine

Metolachlor

Metals:

Aluminum

Beryllium

Gallium

Molybdenum

Silver

Zinc

Antimony

Arsenic

Cadmium

Cobalt

Lanthanum

Tron

Nickel

Lead*

Strontium

Tellurium

Mercury (in solids)

Barium

Chromium

Lithium

Rubidium

Uranium

Boron

Copper

Manganese

Selenium

Vanadium

.....along with billions of tons of sewage.

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

Although mills had been relying on Niagara River water for a hundred years before Frederic Church cropped out the developments along the river to create his iconic painting of the Falls in 1857, the dramatic deterioration of the river started two years later. A canal was dug around the Falls to power the large mills and manufacturing plants that were built just downstream of the tourist attraction. New York State encouraged the industrial development and unrestricted use of the river so that, by the end of the century, 265 manufacturing plants were creating enough water, ground and air pollution that the environment was unhealthy for the residents of the region and was creating an eyesore to the growing tourism industry. Without enforced regulations or urban planning to take care of the sewage from the growing population along the river and Lake Erie, the toxicity of the region worsened. Over the century that followed, the scale of the pollution became so insurmountable that it was impossible to secure enough funding to resolve the situation. To make matters worse, toxic contaminants continue to leak from toxic dump sites, brownfield and superfund sites. Toxic waste from industrial plants continues to flow into the river and municipalities continue to unload billions of tons of sewage into the river and its tributaries every year. This is the same river that is the source of public water for several cities. The past few decades, however, have shown that when the government supports clean-up efforts through funding, when regulatory policies are followed and enforced, and when the public is made aware of the situation, significant improvements can occur. Mussels (Elliptio complanata) filter small organic particles out of the water column and by doing so they can be used to monitor the concentrations of contaminants, to identify contaminant sources and to document effectiveness of remedial actions.

Some of the toxins you will find in the river are as follows:

Chlorobenzenes (CBs):

1,3-Dichlorobenzene

1,4-Dichlorobenzene

1,2-Dichlorobenzene

1,3,5-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,3-Trichlorobenzene

1,2,3,4-Tetrachlorobenzene

Pentachlorobenzene

Hexachlorobenzene

Organochlorine Pesticides (OCs):

α-HCH

α-Chlordane1

p,p’-DDT2

γ-HCH (lindane)

γ-Chlordane

o,p-DDT

Heptachlor

Methoxychlor

p,p’-DDE

Heptachlor-epoxide

Aldrin

Endrin Aldehyde

p,p’-TDE

β-Endosulfan

Endrin

α-Endosulfan

Dieldrin

PCBs

Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs):

2-Methylnaphthalene

1-Methylnaphthalene

Chrysene/Triphenylene

2-Chloronaphthalene

Naphthalene

Anthracene

Fluorene

Phenanthrene

Pyrene

Dibenzo(ah)anthracene

Fluoranthene

Benzo(b/k)fluoranthene 3

Benzo(a)pyrene

Indeno(123-cd)pyrene

Benzo(ghi)perylene

Acenaphthylene

Benzo(a)anthracene

Industrial By-product Chemicals:

Octachlorostyrene

Mirex

Photomirex

Hexachlorobutadiene

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene

Herbicides:

Atrazine

Metolachlor

Metals:

Aluminum

Beryllium

Gallium

Molybdenum

Silver

Zinc

Antimony

Arsenic

Cadmium

Cobalt

Lanthanum

Tron

Nickel

Lead*

Strontium

Tellurium

Mercury (in solids)

Barium

Chromium

Lithium

Rubidium

Uranium

Boron

Copper

Manganese

Selenium

Vanadium

.....along with billions of tons of sewage.

5. Biological Regionalism: Birds of the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

In 1996, the Niagara River Corridor was classifies as a Globally Significant Important Bird Area.. The 32 miles of the Niagara River which connect Lake Erie to Lake Ontario’s provide a tremendous and unique habitat for numerous species of flora and fauna. These include 45 wildlife species that are protected by New York State and at least 21 rare and threatened species, such as Blanding's turtle, Lake Sturgeon, Black-capped Petrel and the Piping Plover. The petrol and plover are both protected federally in the US. The river also provides an important migratory corridor for arctic and neotropical birds and supports one of the largest and most diverse concentrations of gulls in the world. A total of 19 gull species (included in the painting) or 60 percent of world’s gull species inhabit the river each year. Over 100,000 Bonaparte's Gull and Herring Gull have been estimated to migrate through the corridor annually or over 25% of their global populations. On single days, around 14 percent of the North American American Herring Gulls have been reported on the site. Up to 92 bird species overwinter along the river along with large populations of 40 waterbird species.

This unique ecosystem has been in existence since the last ice age, but since the last century it has experienced significant threats from the pollution created by industry, agriculture and urban development. Restoring and protecting the habitat of this globally significant region is critical to the survival and well being of its floral and fauna (including humans).

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

In 1996, the Niagara River Corridor was classifies as a Globally Significant Important Bird Area.. The 32 miles of the Niagara River which connect Lake Erie to Lake Ontario’s provide a tremendous and unique habitat for numerous species of flora and fauna. These include 45 wildlife species that are protected by New York State and at least 21 rare and threatened species, such as Blanding's turtle, Lake Sturgeon, Black-capped Petrel and the Piping Plover. The petrol and plover are both protected federally in the US. The river also provides an important migratory corridor for arctic and neotropical birds and supports one of the largest and most diverse concentrations of gulls in the world. A total of 19 gull species (included in the painting) or 60 percent of world’s gull species inhabit the river each year. Over 100,000 Bonaparte's Gull and Herring Gull have been estimated to migrate through the corridor annually or over 25% of their global populations. On single days, around 14 percent of the North American American Herring Gulls have been reported on the site. Up to 92 bird species overwinter along the river along with large populations of 40 waterbird species.

This unique ecosystem has been in existence since the last ice age, but since the last century it has experienced significant threats from the pollution created by industry, agriculture and urban development. Restoring and protecting the habitat of this globally significant region is critical to the survival and well being of its floral and fauna (including humans).

6. Biological Regionalism: Niagara Falls on the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

The beauty and wonder of Niagara Falls has seduced countless individuals into trying to record the site and their emotions through whatever means they had on hand. I visited the Falls well over a dozen times, since I arrived in the region in 1989 and have painted the cataract several different times in various different series. Each time, I envisioned Niagara Falls as an iconic symbol for American popular culture. As a refugee from Cuba, I also saw it as a metaphor for my new “home” as an idealized reflection of it. With every visit, I was more in awe of the Falls’ power and natural beauty but it became increasingly difficult to experience its natural aesthetics due to the distracting commercialization that bordered it. I longed to experience a time when the Falls was less tainted by this development and sought out the paintings, drawing, and prints of this region during the 18th and 19 century. I was moved by several artists’ depictions of the site, and I have made simple drawings of these 36 works along the edges of this painting. These artists include: Frederic Edwin Church, Louis Rémy Mignot, Herman Herzog, Thomas Hill, James Pattison Cockburn, Albert Bierstadt, Jasper Francis Cropsey, George Innes, Richard Wilson, John Frederick Kensett, Ferdinand Richardt, John Vanderlyn, Samuel Finley Breese Morse, Alan T. Fisher, and Thomas Pritchard Rossiter. My version of the Falls reflects what I have learned about its history and present condition and incorporates my feelings about this enlightenment. It was created by looking at photos from 1969 when water was diverted from the American Falls for excavation and scientific metering, from bathymetric maps (underwater topographical maps) and from scientific sources. Nature remains powerful through its geology. The water is no longer wild and is removed exposing the journey the Falls has traveled.

As is the case with most of the paintings, the imagery is created by researching various resources including drawing and photographs I created on site, government reports, topographical maps, and tourist images of the Falls over previous decades.

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

The beauty and wonder of Niagara Falls has seduced countless individuals into trying to record the site and their emotions through whatever means they had on hand. I visited the Falls well over a dozen times, since I arrived in the region in 1989 and have painted the cataract several different times in various different series. Each time, I envisioned Niagara Falls as an iconic symbol for American popular culture. As a refugee from Cuba, I also saw it as a metaphor for my new “home” as an idealized reflection of it. With every visit, I was more in awe of the Falls’ power and natural beauty but it became increasingly difficult to experience its natural aesthetics due to the distracting commercialization that bordered it. I longed to experience a time when the Falls was less tainted by this development and sought out the paintings, drawing, and prints of this region during the 18th and 19 century. I was moved by several artists’ depictions of the site, and I have made simple drawings of these 36 works along the edges of this painting. These artists include: Frederic Edwin Church, Louis Rémy Mignot, Herman Herzog, Thomas Hill, James Pattison Cockburn, Albert Bierstadt, Jasper Francis Cropsey, George Innes, Richard Wilson, John Frederick Kensett, Ferdinand Richardt, John Vanderlyn, Samuel Finley Breese Morse, Alan T. Fisher, and Thomas Pritchard Rossiter. My version of the Falls reflects what I have learned about its history and present condition and incorporates my feelings about this enlightenment. It was created by looking at photos from 1969 when water was diverted from the American Falls for excavation and scientific metering, from bathymetric maps (underwater topographical maps) and from scientific sources. Nature remains powerful through its geology. The water is no longer wild and is removed exposing the journey the Falls has traveled.

As is the case with most of the paintings, the imagery is created by researching various resources including drawing and photographs I created on site, government reports, topographical maps, and tourist images of the Falls over previous decades.

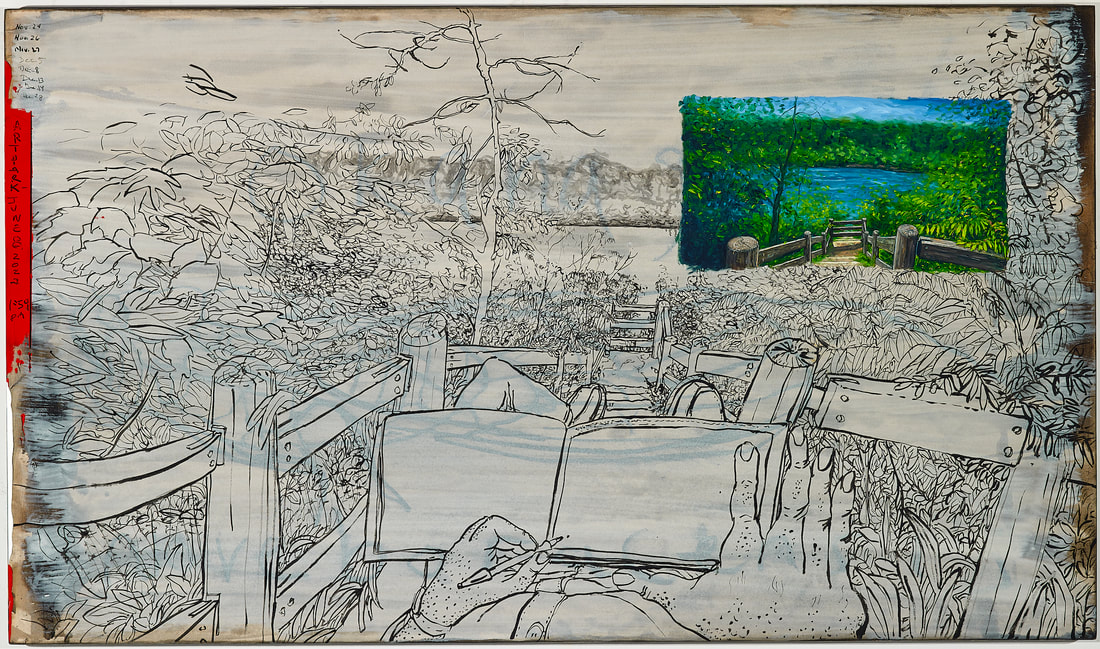

7. Biological Regionalism: Artpark on the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

This painting depicts one of my favorite locations on the Niagara River. The site of this painting is easily accessible from Artpark, a 150-acre New York State Park and renowned venue for the visual and performing arts. It is located at the intersection of the Niagara Escarpment, the gorge walls of the Niagara River and the lower plain of Lewiston. The trail, from the park, periodically goes through canopies of Red Oak, Birch, Sugar Maple, Basswood, White Ash, Bing Cherry and Black Walnut trees providing intimate opportunities from which to experience the power and beauty of the river.

The drawing for this painting was created on June 8th, 2022 at 1:59 pm when it was 72 degrees. Underneath this oil painting and drawing, is the ghost image of a drawing of one of the rarest species of cicada, Okanagana noveboracensis or Niagara Cicada. It cannot be found anywhere else in the world apart from the Niagara Gorge. The Niagara River and its unique ecosystem is home to many threatened and endangered species. One of the challenges of this project was selecting from the thousands of interesting and important scientific and cultural stories about the Niagara River.

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

This painting depicts one of my favorite locations on the Niagara River. The site of this painting is easily accessible from Artpark, a 150-acre New York State Park and renowned venue for the visual and performing arts. It is located at the intersection of the Niagara Escarpment, the gorge walls of the Niagara River and the lower plain of Lewiston. The trail, from the park, periodically goes through canopies of Red Oak, Birch, Sugar Maple, Basswood, White Ash, Bing Cherry and Black Walnut trees providing intimate opportunities from which to experience the power and beauty of the river.

The drawing for this painting was created on June 8th, 2022 at 1:59 pm when it was 72 degrees. Underneath this oil painting and drawing, is the ghost image of a drawing of one of the rarest species of cicada, Okanagana noveboracensis or Niagara Cicada. It cannot be found anywhere else in the world apart from the Niagara Gorge. The Niagara River and its unique ecosystem is home to many threatened and endangered species. One of the challenges of this project was selecting from the thousands of interesting and important scientific and cultural stories about the Niagara River.

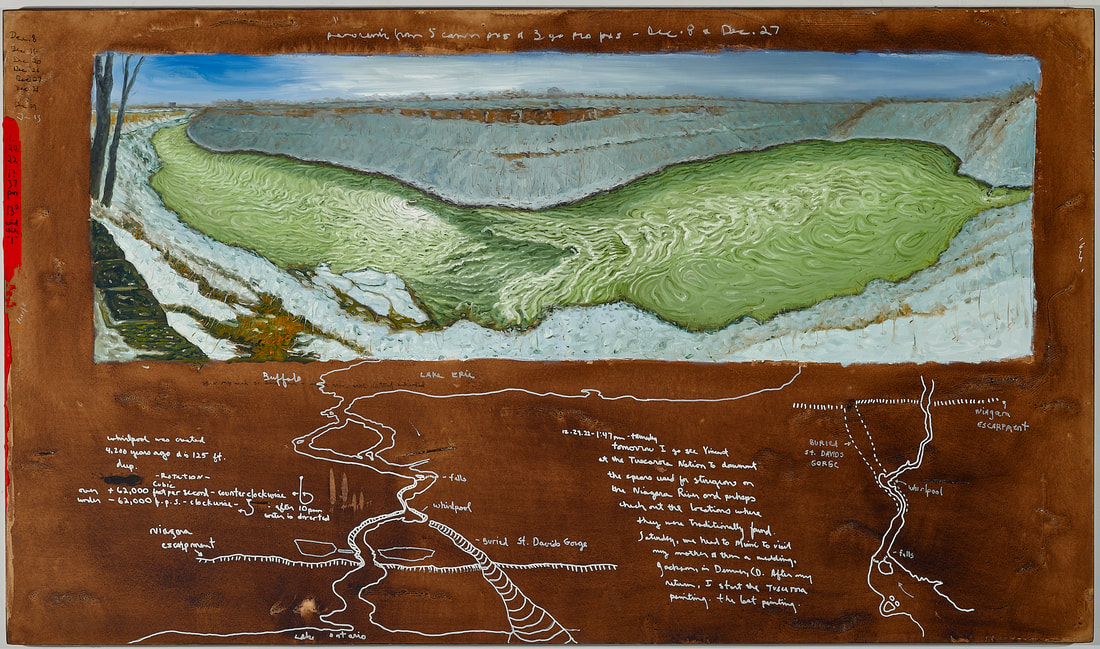

8. Biological Regionalism: Whirlpool Rapids and Whirlpool of the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

$7000

Courtesy of Meibohm Fine Arts

Approximately 18,000 years ago this area was covered by ice sheets that were close to two miles thick. As the sheets moved southward they scoured out the Great Lakes and as they retreated back north 12,500 ago, they left behind most of the water that remains in the Lakes to this day. The melting waters created five rivers between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario but over time, they were reduced to one, the Niagara River. Niagara Falls was formed as the water flowed over the Niagara Escarpment, a cliff that runs a steep slope east/west from New York through Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois. The location of the Falls origin is where Lewiston, New York is located today. A couple of thousand years later, glaciers continued to move and alter the geology so that most of the of the melting waters were rerouted northward bypassing the Niagara River. For 5,000 years, the Niagara River had only ten percent of its flow and Lake Erie was half the size it is today. About 5,500 years ago, the waters were gradually routed back south to the Niagara River. Niagara Falls continued to move upstream as it eroded the river’s bedrock. When it reached the Whirlpool area around 4,200 years ago, it violently intersected with the old Saint David’s riverbed. The Saint David’s River was an ancient pre-glacial river bed that existed 22,800 years ago. It extended into what is now Lake Ontario and was 200 feet deeper than the lake’s current depth. When the glaciers retreated 12,000 years ago, they filled the river and gorge with silt and rocks. When the Falls reached the location of the ancient river, it slammed into the walls of the buried gorge and dug out the glacial silt until it reached the ancient river’s bottom. By this point the falls had collapsed into a huge churning set of rapids. For two hundred years, the water downstream of the river and into Lake Ontario remained muddy. When the scouring had finished, the Falls continued to move upstream to its present location, but it had left behind the 90-degree turn in the river and the set of rapids upstream of the bend that produces North America’s largest series of standing waves when the river is flowing at its height.

"Dyunowadase" is what the Senecas named the Whirlpool. It translation is "the current goes around." For thousands of years, the current in the Whirlpool rotated counterclockwise. Since 1973, it has reversed its current so that now flows clockwise during most of the year except for the tourists months (June, July, and August). During these tourist months, it reverses again between 10pm and 8am. This reversal of the natural flow of the river is cause by the diversion of water to nearby power plants. The average flow of the Niagara River is around 202,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) which is an incredible amount of water when one considers that all of the major streams in Western New York average between 30-350 cfs. Most of the year, however, the flow to Niagara Falls and the Whirlpool is reduced to 50,000 cfs or 25% of the river’s average amount of water. Even during peak tourist hours, the flow is running at 100,000 cfs or half of the river’s natural amount. When the flow drops below 65,000 cfs, the rotation of the current in the Whirlpool begins to change. The documentation to create this painting was collected on January 20, 2022 when the current was slowly flowing clockwise. There has been some interesting research that has begun over the past decade about how the Whirlpool naturally cleans some of the water in the river by collecting higher amount of toxins in the froth that is formed by the Rapids and the Whirlpool.

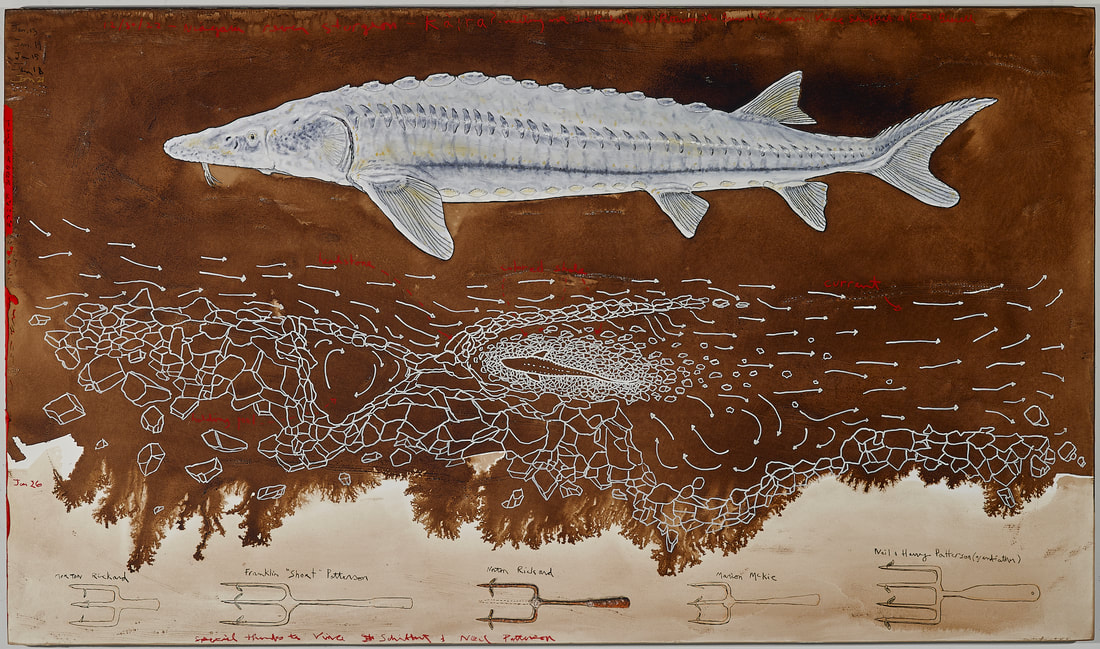

9. Biological Regionalism: Tuscarora Tradition of Sturgeon Spearfishing in the Niagara River, United States of America / Canada

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

On June 8, 2022, I met Vince Schiffert at the Tuscarora Elementary School in Lewiston, New York where he had just finished teaching one of his classes. He was generous with his time and over the two hours we spent together, outlined the cultural history of the Tuscarora and the traditions and rituals that have evolved over the past centuries. He also showed me a recent video produced by Tuscarora biologists, and community members about tribal spear fishing traditions on the Niagara River.

December 30th, 2022, I met again with Vince at the Tuscarora Health Center Tuscarora Community across the street from the Tuscarora Elementary School. He introduced to me to Joseph Rickard, Neil Patterson Jr., Brennan Ferguson, and Pete Bissell. Over the next four hours, they discussed the detailed practice of spear fishing for sturgeon and other species, the creation of docks or weirs over the centuries, the handmade process of manufacturing spears, the change in water quality on the Niagara River, and the change in state fishing policies as related to tribal rights. I was moved by their generosity with their time, their expertise and their efforts in recalling past memories on the river.

One of the many memorable stories from that afternoon occurred in the 1970’s. Joseph mentioned that after working all day in one of the chemical plants that lined the banks of the Niagara River, he would go down to the river and spend the evenings spear fishing for sturgeon. He remembered how the air over the river was filled with the same pungent smells that he experienced during the day in the chemical plants. It was also the same smell that he found when he opened the body cavity of salmon and sturgeon. The banks of the river were sporadically lined with the dim yellow lights of kerosene lanterns. Each tribal family waited for sturgeon to swim up near the banks into the weirs that had been created and maintained for generations. He remembered how peaceful and silent it was apart from the subtle sound of slow moving water and the periodic "jooch" sound of a spear penetrating the water toward a sturgeon. The word signifying this sound, that had been heard for hundreds of years, is listed in the Tuscarora language dictionary.

The weirs or docks are located throughout the banks the Niagara River. These docks were created centuries ago and maintained annually over the generations by tribal anglers. The docks use naturally occurring rock formations that break into the river and are constructed at locations just upstream of eddies. The last large rock that juts into the river is called the headstone. Additional rocks are added from the headstone into the river to create a “V” shape pointing upstream. Every year additional rocks are added to the wall since ice and heavy current break down the formation. The rock wall creates a barrier that slows down the water and allows sturgeon, salmon and bait fish to rest behind it as they move upstream. Buckets of colored shale are deposited just upstream of the headstone so that when they fall through the current they settle behind the headstone and in the middle of the “V”. The drifting shale also provides the angler with an indication of strength of the current and the angle to use when throwing the spear at the sturgeon. The colored shale on the river bed is used as a background to better identify a contrasting colored sturgeon as it swims above it. The loose shale bottom also provides a softer surface to prevent damage to a spear if it misses its target. The soft light of the kerosene lamps shed light on the water while not spooking the sturgeon. The light can also imitate moonlight. When the sturgeon swims from the eddy along the bank and into the “v” shaped dock, the angler can see the contrasting shape against the riverbed and throws the fourteen foot spear. Each tribal family has their own spear design. These spear fishing families include the Rickard, Patterson, Bissell, Green, Hewitt, Printup, Hill, Jacobs, and Henry families.

If the spear reaches and penetrates the sturgeon, the angler then begins to fight the fish with the rope that is attached to the spear. Once the handle of the spear can be reached, the sturgeon is pulled up into the holding pool located along the bank upstream of the dock. The Tuscarora name for sturgeon is also the same name given to the dandelion or strawberry blossom. When the plants blooms, it indicates that it is time to fish for sturgeon.

Materials, images and information curated for this exhibit support ongoing cultural practices by Tuscarora people on the Niagara River.

42” x 72”

Niagara River water, walnut ink, oils, pastels, and charcoal on 300 lb Lanaquarelle paper on board

On June 8, 2022, I met Vince Schiffert at the Tuscarora Elementary School in Lewiston, New York where he had just finished teaching one of his classes. He was generous with his time and over the two hours we spent together, outlined the cultural history of the Tuscarora and the traditions and rituals that have evolved over the past centuries. He also showed me a recent video produced by Tuscarora biologists, and community members about tribal spear fishing traditions on the Niagara River.

December 30th, 2022, I met again with Vince at the Tuscarora Health Center Tuscarora Community across the street from the Tuscarora Elementary School. He introduced to me to Joseph Rickard, Neil Patterson Jr., Brennan Ferguson, and Pete Bissell. Over the next four hours, they discussed the detailed practice of spear fishing for sturgeon and other species, the creation of docks or weirs over the centuries, the handmade process of manufacturing spears, the change in water quality on the Niagara River, and the change in state fishing policies as related to tribal rights. I was moved by their generosity with their time, their expertise and their efforts in recalling past memories on the river.

One of the many memorable stories from that afternoon occurred in the 1970’s. Joseph mentioned that after working all day in one of the chemical plants that lined the banks of the Niagara River, he would go down to the river and spend the evenings spear fishing for sturgeon. He remembered how the air over the river was filled with the same pungent smells that he experienced during the day in the chemical plants. It was also the same smell that he found when he opened the body cavity of salmon and sturgeon. The banks of the river were sporadically lined with the dim yellow lights of kerosene lanterns. Each tribal family waited for sturgeon to swim up near the banks into the weirs that had been created and maintained for generations. He remembered how peaceful and silent it was apart from the subtle sound of slow moving water and the periodic "jooch" sound of a spear penetrating the water toward a sturgeon. The word signifying this sound, that had been heard for hundreds of years, is listed in the Tuscarora language dictionary.

The weirs or docks are located throughout the banks the Niagara River. These docks were created centuries ago and maintained annually over the generations by tribal anglers. The docks use naturally occurring rock formations that break into the river and are constructed at locations just upstream of eddies. The last large rock that juts into the river is called the headstone. Additional rocks are added from the headstone into the river to create a “V” shape pointing upstream. Every year additional rocks are added to the wall since ice and heavy current break down the formation. The rock wall creates a barrier that slows down the water and allows sturgeon, salmon and bait fish to rest behind it as they move upstream. Buckets of colored shale are deposited just upstream of the headstone so that when they fall through the current they settle behind the headstone and in the middle of the “V”. The drifting shale also provides the angler with an indication of strength of the current and the angle to use when throwing the spear at the sturgeon. The colored shale on the river bed is used as a background to better identify a contrasting colored sturgeon as it swims above it. The loose shale bottom also provides a softer surface to prevent damage to a spear if it misses its target. The soft light of the kerosene lamps shed light on the water while not spooking the sturgeon. The light can also imitate moonlight. When the sturgeon swims from the eddy along the bank and into the “v” shaped dock, the angler can see the contrasting shape against the riverbed and throws the fourteen foot spear. Each tribal family has their own spear design. These spear fishing families include the Rickard, Patterson, Bissell, Green, Hewitt, Printup, Hill, Jacobs, and Henry families.

If the spear reaches and penetrates the sturgeon, the angler then begins to fight the fish with the rope that is attached to the spear. Once the handle of the spear can be reached, the sturgeon is pulled up into the holding pool located along the bank upstream of the dock. The Tuscarora name for sturgeon is also the same name given to the dandelion or strawberry blossom. When the plants blooms, it indicates that it is time to fish for sturgeon.

Materials, images and information curated for this exhibit support ongoing cultural practices by Tuscarora people on the Niagara River.